Ever since watching the terrible video of a student being pulled from her desk and thrown to the ground, I've been waiting to learn how disability intersected with this case. I assumed it would, because the data shows that the two groups most vulnerable to violence at the hands of school authorities are people of color and students with disabilities.

Disabled people of color are multiply marginalized, and thus highly at risk - see my pieces

here and

here.

|

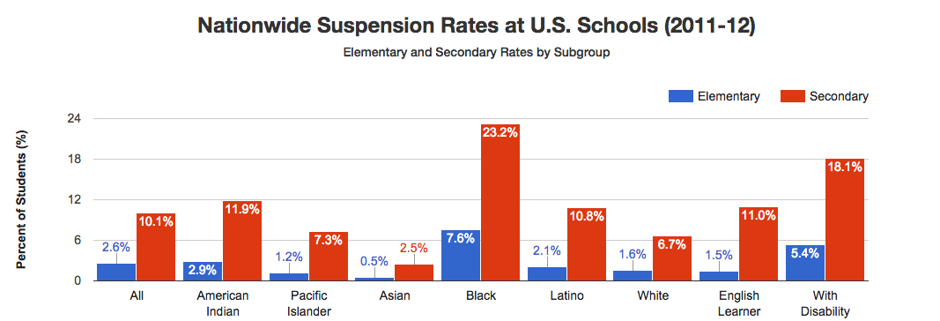

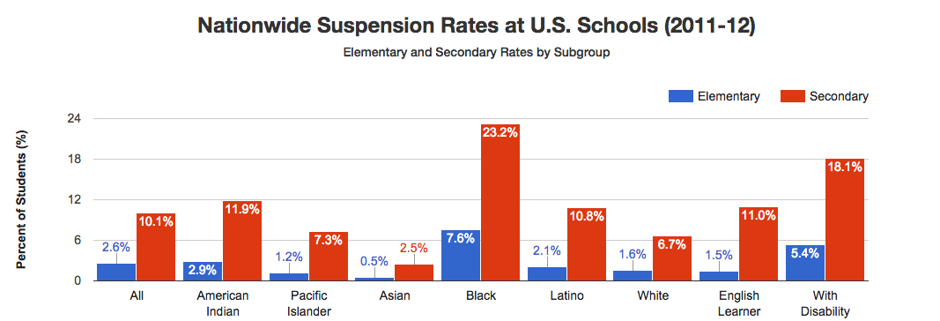

Chart from http://www.citylab.com/crime/2015/10/why-disabled-students-suffer-at-the-hands-of-classroom-cops/412723/

It shows 22.3% of all suspensions are black students. 18.1% are disabled. |

Once we learned that school resource officer Ben Fields was known as "Officer Slam," I knew that if we dug into this officer's background, we'd find disabled victims of his bullying. That's just what happened. Here's a story that describes

his violent encounter with an autistic student [my emphasis]:

Richland School District Two Superintendent Debbie Hamm admits that "clearly something did not go right," calling it the most upsetting incident she has seen in her 40 years with the district.

"We will be working with the Richland County Sheriff's Office to clarify our expectations about screening and training for school resource officers," said Hamm.

But one parent had a slightly different reaction.

"I saw his face and my first thought was 'Oh my god, that's the same guy,'" said Wendy Johnson, who says her autistic son was in a physical struggle with Fields when he was a freshman.

Photos she took of her son after the altercation reveal his shirt torn and marks on his arms and shoulder.

Notice how the Superintendent characterizes the assault on the video as out of the norm. My guess is that "Officer Slam" does this all the time, it's just now he's being held accountable. The violence is structural. The violence is systemic. This is not an isolated incident.

Then there's the question of trauma. There's a major class-action lawsuit in California arguing that victims of trauma

should be covered under disability law. It has enormous implications for American education, because up to a quarter of all children, according to Susan Ko of the

National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, will be victims of trauma. If trauma is so common and if should be treated as a disability (both givens that I believe to be true), it may indeed force us to stop treating disability as a deviation from the norm, as a case of "special" needs, but just as needs. We'll have to move to a system of universal design that requires all interactions with students take the possibility of disability into account.

I don't know whether the student dragged out of her desk was a victim of trauma.

I don't need to know. Initial reports was that she was a recent orphan, more recent information is that she is estranged from her mother and living in foster care, and now that narrative

has been questioned too. We, as a nation, are overly fond of litigating the character of the victim of state violence as a way of determining whether or not they deserved to be brutalized. Such violence is not determined by whether she was a "good victim" or not, but instead whether she was in fact engaged in threatening behavior that merited escalating use of force. Judging by the videotape, she was not. Case closed.

Her lawyer does say that she's a victim of trauma now, in considerable emotional distress. I believe it. The assault looks traumatizing. Having millions of people view your assault, likewise.

In that classroom, the statistics suggest, there surely were people who had experienced trauma, and who had to observe the violence.

That's only going to make matters worse.

Many traumatized students live in a state of constant alarm. Innocent interactions like a bump in the hallway or a request from a teacher can stir anger and bad behavior

The lawsuit alleges that, in Compton, the schools' reaction to traumatized students was too often punishment — not help.

"They were repeatedly either sent to another school, expelled or suspended — and this went back to kindergarten," says Marleen Wong, who teaches at the USC School of Social Work and has spent decades studying kids and trauma. "I think we're really doing a terrible disservice to these children."

The suit argues that trauma is a disability and that schools are required — by federal law — to make accommodations for traumatized students, not expel them. The plaintiffs want Compton Unified to provide teacher training, mental health support for students and to use conflict-mediation before resorting to suspension.

We must get these SROs - School Resource Officers - out of the schools. We cannot respond to the prevalence of trauma with more police officers, more violence, or zero tolerance policies. It's counter-productive. Hopefully, the courts will also decide that it violates the ADA.